MATEO CHACÓN ORDUZ

Deputy Editor of Vida - Environment

En este portal utilizamos datos de navegación / cookies propias y de terceros para gestionar el portal, elaborar información estadística, optimizar la funcionalidad del sitio y mostrar publicidad relacionada con sus preferencias a través del análisis de la navegación. Si continúa navegando, usted estará aceptando esta utilización. Puede conocer cómo deshabilitarlas u obtener más información aquí

MI CUENTA

No eres suscriptor activo

Suscríbete ahora por sólo $900eres suscriptor digital

> Consulta tu suscripcióneres suscriptor digital pro

> Consulta tu suscripción¡Hola !, Tu correo ha sido verficado. Ahora puedes elegir los Boletines que quieras recibir con la mejor información.

Bienvenido , has creado tu cuenta en EL TIEMPO. Conoce y personaliza tu perfil.

Hola Clementine el correo [email protected] no ha sido verificado. Verificar Correo

El correo electrónico de verificación se enviará a

Revisa tu bandeja de entrada y si no, en tu carpeta de correo no deseado.

Ya tienes una cuenta vinculada a EL TIEMPO, por favor inicia sesión con ella y no te pierdas de todos los beneficios que tenemos para tí. Iniciar sesión

Ecosystems: The Climate Thermometers

In January of this year, one of the last glaciers of Nevado Santa Isabel disappeared, and the rest will not last beyond 2030. Meanwhile, Jorge Luis Ceballos continues his mission to record the melting of the country's six snow-capped peaks.

"I'm running out of work," warns Jorge Luis Ceballos, the only glaciologist working for Ideam and the person who has tracked Colombia's six snow-capped peaks the longest (25 years) and is the main witness to their increasingly slow melting.

"It is like arriving at the office and seeing that there is no office anymore. Glaciologists in the world are already an endangered species, and in the case of Colombia I am the only one," explains Ceballos in an interview with EL TIEMPO, as he recounts how, one by one, the country's snow-capped peaks are losing their ice cover. One of them, according to the expert, is already doomed to disappear completely: El Nevado de Santa Isabel (located between Risaralda, Tolima and Caldas).

It is estimated that by 2030, this 4,965-meter peak (the lowest in the country) will have completely lost its glacier cap. It will no longer make sense to call it as some locals still do: Poleka Kasué, which means "white maiden" in the Quimbaya language.

"This is high school science: the temperature at which water freezes and becomes ice is 0 degrees Celsius. Above that, it melts. And if we put a thermometer in Santa Isabel, we see that the constant temperature is between 2 and 5 degrees Celsius. This is a temperature where the glacier clearly has no choice but to melt," says Ceballos.

It is estimated that in the middle of the 19th century, the Santa Isabel glacier covered about 27 square kilometers. One hundred years later, 9.4 square kilometers remained, but the latest calculations by Ideam estimate that there is currently only 0.29 square kilometers of ice. This means that in 70 years, 96% of the ice on this peak has been lost, a situation that has accelerated since 2016 (due to the strong El Niño phenomenon of that year): in eight years, two thirds of the remaining glacier disappeared.

Moreover, it is no longer a single ice sheet, but several fragmented miniglaciers. Two of them (Otún Norte and Otún Sur) became extinct in 2022, and another (Conejeras) disappeared at the beginning of this year. Thus, Santa Isabel went from nine to six "glaciers" in just two years.

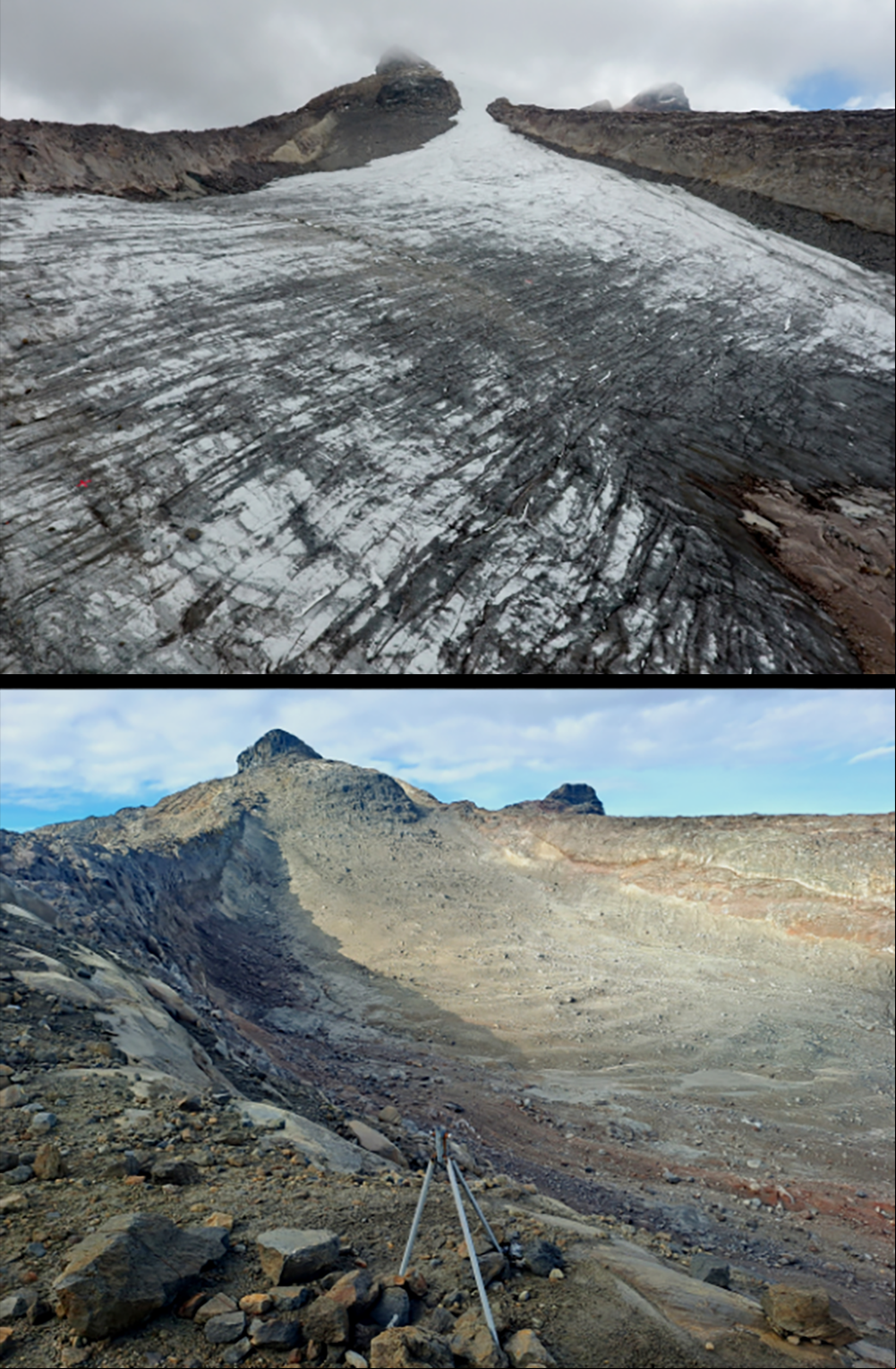

Extinction of the glacier in the Conejeras sector between 2018 (above) and 2024 (below).PHOTO: Jorge Luis Ceballos. IDEAM.

According to the expert, we are living in a historical and irreversible moment from which we can only learn. What were once great ice sheets are giving way to the páramo: one ecosystem is dying to make way for another. There is no way to recover it; the snowfalls are less frequent and insufficient, the thaw leaves a thick layer of volcanic ash that makes it even more difficult to compress the crystals and, as Ceballos says, this peak has the altitude against it. At an altitude of less than 5,000 meters, the chances of temperatures falling below 0°C for a sustained period are almost nil.

Santa Isabel is the most dramatic case, but not the only one. In fact, Ideam estimates that by 2100 there will be no snow-capped peaks left in Colombia. Currently, the country's glacier cover is 33 km², only a tenth of what it was in the mid-nineteenth century and half of what it was in the nineties. And it seems incredible how the art of previous centuries (historical records of what these frozen masses were) showed huge Andean peaks adorned in white almost to their skirts.

"Fortunately, in the other five snow-capped peaks in the country (Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Sierra Nevada del Cocuy, and the snow-capped volcanoes of Ruiz, Huila, and Tolima), the rest of the glacier layer is above 5,000 meters above sea level, which does not guarantee that they will survive, but they will survive a little longer," says Ceballos.

But just because they are at that altitude does not mean that they have not suffered the ravages of climate change, especially the El Niño phenomena of 2016 and last year, which have significantly affected the glacier layer.

A clear example is the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, which is severely affected by temperature changes in the Caribbean. It is a mystery to scientists because Ideam's instruments cannot reach it because it is sacred indigenous land, so it can only be studied with satellite images. These show that it is losing about 5 percent of its area each year. Today it covers 5.3 km².

The best preserved peak is the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy (also known as Güicán), with 12.8 km² and about 5,400 meters high. It is probably the one that will survive the longest because it has the good fortune to be influenced by the Andean and Orinoco zones, so that while there is a dry season on one side, there is a wet season on the other, making it less susceptible to hot and dry seasons.

This is not the case for the country's three snow-capped volcanoes: Ruiz, Huila and Tolima. Although their altitude favors them, their melting has accelerated in recent years, and they have lost half of their surface area in the last 30 years. The most dramatic case of these three is that of Tolima, whose extension today is barely 0.5 km², surely the next to become extinct after Santa Isabel.

Changes in glacial coverage, Nevado Santa Isabel volcano.PHOTO: IDEAM

"I would say that it is a miracle that we have snow-capped mountains in Colombia," says the glaciologist expert. And indeed, the fact that the country has this type of ecosystem is absolutely unusual.

No wonder. In the world there are only three regions on the equatorial line that have a layer of glaciers. They are Colombia and Ecuador, a small region of Africa (where Mount Kilimanjaro is located), and Indonesia.

And they are so rare in these equatorial zones because the few glaciers that exist there are conditioned by factors such as being in the Intertropical Confluence Zone (characterized by higher temperatures) and a different exposure to solar radiation, not to mention that there are no seasons, no long snow seasons, or constant cold.

As a result, the dynamics of the glaciers as an ecosystem are very different, because unlike in other latitudes, where snow-capped peaks are the source of water, here the water supply depends more on rivers and tributaries that originate in the páramos. And this is encouraging, says Ceballos, because the lack of ice does not imply water scarcity, as is the case in European countries, for example.

This makes the study of glaciers in countries like Colombia different, but no less important. The six small glaciers that Colombia currently has, although relatively insignificant in the global balance of glaciers, but because they are equatorial glaciers, are the "thermometers of the world", a thermal indicator that shows how much the planet is warming, a reminder that if humanity continues on the same path, what is happening today in the Santa Isabel could happen in the Alps, the Andes or the Himalayas.

It is more than the loss of the landscape, it is the loss of an entire ecosystem that, inhospitable as it may seem, is still important for the thermal regulation of the planet.

"We are facing a historic moment. We have no choice but to learn from it, to visit the snow-capped mountains that are still visible, to witness the last of the ice that we have left. Imagine telling your grandchildren that you personally saw ice on the tops of the mountains! Snow in Colombia! How is that possible?" says Ceballos.

He adds: "It is sad that my life's work is disappearing, but just as one ecosystem dies and another is born, a profession disappears, but now more biologists and environmental engineers will be needed to study the effects of this change. For my part, I can say that I lived under the ice in a tropical country and witnessed an event that will go down in history".

MATEO CHACÓN ORDUZ

Deputy Editor of Vida - Environment

Swipe left to navigate

The waters are affected by illegal mining and uncontrolled deforestation, and have become garbage dumps.

The country's high courts have ruled in favour of reducing the impact on ecosystems. The precautionary principle and payments for environmental damage are among the rulings.

The project is located in the community of Toca and is led by women. The initiative comes from the World Economic Forum and aims to make life on the land more profitable and sustainable by using data science and changing traditional practices.

On Saturday, October 26, a salsa legend will be the main guest of the event, which will take place at the Pascual Guerrero Stadium.

These charts are in their original Spanish version.

According to the criteria of

Since Cali was confirmed as the venue for COP16, EL TIEMPO has been covering all the preparations and decisions for the event. And it will continue to do so in the weeks leading up to the event, during its development and in the aftermath of its decisions.

The multimedia coverage was unveiled on Monday, September 2, and will continue daily for at least two months. In the print pages and digital platforms, people will be able to find all the information related to this summit, exclusive interviews, analysis and special reports. In addition, a high graphic content, with explanations, data and X-rays that give an of the current situation of biodiversity in Colombia and the planet, the challenges for how humanity acts and what is being done to preserve and conserve fauna, flora and ecosystems.

The information comes from official sources involved in the development of the event, such as the Ministries of Environment, Culture and Foreign Affairs, the Mayor's Office of Cali and the Governor's Office of Valle del Cauca, and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).

From October 21st to November 1st, a 15-member multimedia news team will be responsible for covering the Summit events, the dialogues between the heads of state and the delegations of the participating countries, and the parallel activities that will take place. In addition, an exclusive e-mail newsletter will provide ed s with first-hand, confirmed and updated information.

Convention on Biological Diversity https://www.cbd.int/

COP16 Colombia, official website https://www.cop16colombia.com/es/

UN Environment Program https://www.unep.org/es

Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development of Colombia https://www.minambiente.gov.co/

Ministry of Culture of Colombia https://www.mincultura.gov.co/

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Colombia https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/

Mayor's Office of Cali https://www.cali.gov.co/

Center for Sustainable Development Goals, Universidad de Los Andes https://cods.uniandes.edu.co/

National Network of Open Data on Biodiversity (SiB) https://biodiversidad.co/

Biodiversity Reports and Collections, Humboldt Institute http://reporte.humboldt.org.co/ biodiversidad/

BBC Earth collections and reports https://www.bbcearth.com/

BirdLife International https://datazone.birdlife.org/ country